Prostate Cancer

About Prostate Cancer

Key Points

Prostate cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the prostate.

- Signs of prostate cancer include a weak flow of urine or frequent urination.

- Tests that examine the prostate and blood are used to detect (find) and diagnose prostate cancer.

- Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

- Prostate cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the prostate.

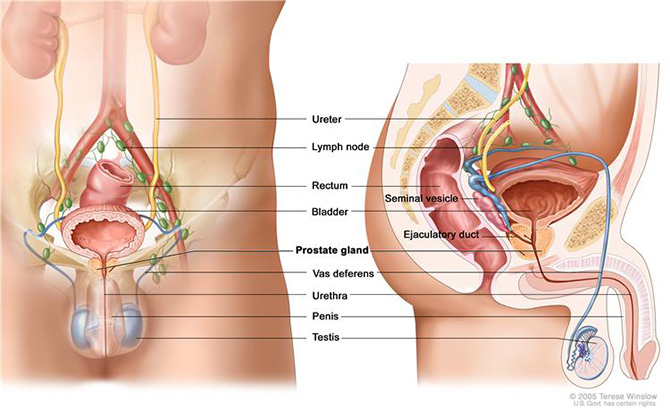

The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system. It lies just below the bladder (the organ that collects and empties urine) and in front of the rectum (the lower part of the intestine). It is about the size of a walnut and surrounds part of the urethra (the tube that empties urine from the bladder). The prostate gland makes fluid that is part of the semen.

Anatomy of the male reproductive and urinary systems, showing the prostate, testicles, bladder, and other organs.

Prostate cancer is found mainly in older men. In the U.S., about 1 out of 5 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Signs of prostate cancer include a weak flow of urine or frequent urination.

These and other signs and symptoms may be caused by prostate cancer or by other conditions. Check with your doctor if you have any of the following:

- Weak or interrupted (“stop-and-go”) flow of urine.

- Sudden urge to urinate.

- Frequent urination (especially at night).

- Trouble starting the flow of urine.

- Trouble emptying the bladder completely.

- Pain or burning while urinating.

- Blood in the urine or semen.

- A pain in the back, hips, or pelvis that doesn’t go away.

- Shortness of breath, feeling very tired, fast heartbeat, dizziness, or pale skin caused by anemia.

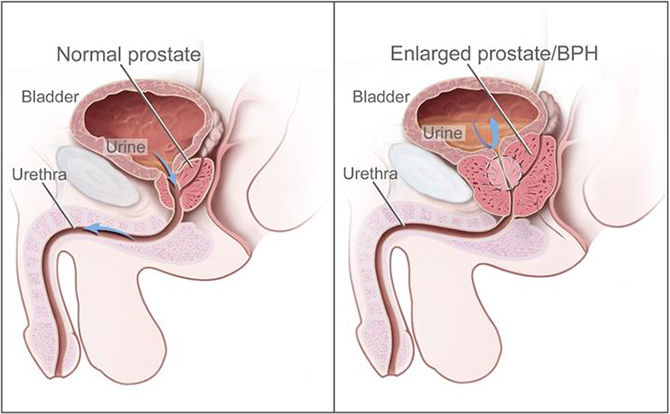

Other conditions may cause the same symptoms. As men age, the prostate may get bigger and block the urethra or bladder. This may cause trouble urinating or sexual problems. The condition is called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and although it is not cancer, surgery may be needed. The symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia or of other problems in the prostate may be like symptoms of prostate cancer.

Normal prostate and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). A normal prostate does not block the flow of urine from the bladder. An enlarged prostate presses on the bladder and urethra and blocks the flow of urine.

Certain factors affect prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

The prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options depend on the following:

The stage of the cancer (level of PSA, Gleason score, grade of the tumour, how much of the prostate is affected by the cancer, and whether the cancer has spread to other places in the body).

- The patient’s age.

- Whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has recurred (come back).

Treatment options also may depend on the following:

- Whether the patient has other health problems.

- The expected side effects of treatment.

- Past treatment for prostate cancer.

- The wishes of the patient.

Most men diagnosed with prostate cancer do not die of it.

Stages of Prostate Cancer

Key Points

After prostate cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the prostate or to other parts of the body.

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

The following stages are used for prostate cancer:

- Stage I

- Stage II

- Stage III

- Stage IV

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

Cancer can spread through tissue, the lymph system, and the blood:

- Tissue. The cancer spreads from where it began by growing into nearby areas.

- Lymph system. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the lymph system. The cancer travels through the lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

- Blood. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the blood. The cancer travels through the blood vessels to other parts of the body.

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

When cancer spreads to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. Cancer cells break away from where they began (the primary tumour) and travel through the lymph system or blood.

- Lymph system. The cancer gets into the lymph system, travels through the lymph vessels, and forms a tumour (metastatic tumour) in another part of the body.

- Blood. The cancer gets into the blood, travels through the blood vessels, and forms a tumour (metastatic tumour) in another part of the body.

The metastatic tumour is the same type of cancer as the primary tumour. For example, if prostate cancer spreads to the bone, the cancer cells in the bone are actually prostate cancer cells. The disease is metastatic prostate cancer, not bone cancer.

The following stages are used for prostate cancer:

As prostate cancer progresses from stage I to stage IV, the cancer cells grow within the prostate, through the outer layer of the prostate into nearby tissue, and then to lymph nodes or other parts of the body.

Stage I

In stage I, cancer is found in the prostate only. The cancer:

- is found by needle biopsy (done for a high PSA level) or in a small amount of tissue during surgery for other reasons (such as benign prostatic hyperplasia). The PSA level is lower than 10 and the Gleason score is 6 or lower; or

- is found in one-half or less of one lobe of the prostate. The PSA level is lower than 10 and the Gleason score is 6 or lower; or

- cannot be felt during a digital rectal exam and cannot be seen in imaging tests. Cancer is found in one-half or less of one lobe of the prostate. The PSA level and the Gleason score are not known.

Stage II

In stage II, cancer is more advanced than in stage I, but has not spread outside the prostate. Stage II is divided into stages IIA and IIB.

In stage IIA, cancer:

- is found by needle biopsy (done for a high PSA level) or in a small amount of tissue during surgery for other reasons (such as benign prostatic hyperplasia). The PSA level is lower than 20 and the Gleason score is 7; or

- is found by needle biopsy (done for a high PSA level) or in a small amount of tissue during surgery for other reasons (such as benign prostatic hyperplasia). The PSA level is at least 10 but lower than 20 and the Gleason score is 6 or lower; or

- is found in one-half or less of one lobe of the prostate. The PSA level is at least 10 but lower than 20 and the Gleason score is 6 or lower; or

- is found in one-half or less of one lobe of the prostate. The PSA level is lower than 20 and the Gleason score is 7; or

- is found in more than one-half of one lobe of the prostate.

In stage IIB, cancer:

- is found in opposite sides of the prostate. The PSA can be any level and the Gleason score can range from 2 to 10; or

- cannot be felt during a digital rectal exam and cannot be seen in imaging tests. The PSA level is 20 or higher and the Gleason score can range from 2 to 10; or

- cannot be felt during a digital rectal exam and cannot be seen in imaging tests. The PSA can be any level and the Gleason score is 8 or higher.

Stage III

In stage III, cancer has spread beyond the outer layer of the prostate and may have spread to the seminal vesicles. The PSA can be any level and the Gleason score can range from 2 to 10.

Stage IV

In stage IV, the PSA can be any level and the Gleason score can range from 2 to 10. Also, cancer:

- has spread beyond the seminal vesicles to nearby tissue or organs, such as the rectum, bladder, or pelvic wall; or

- may have spread to the seminal vesicles or to nearby tissue or organs, such as the rectum, bladder, or pelvic wall. Cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes; or

- has spread to distant parts of the body, which may include lymph nodes or bones. Prostate cancer often spreads to the bones.

Prostate Cancer Diagnosis & Screening

Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA)

PSA is a substance produced almost exclusively in the prostate and plays a role in fertility. The vast majority is actually released into the ejaculate but tiny amounts are released into the bloodstream and can be detected by a simple blood test. Abnormally high levels of PSA can be an indication of disease of the prostate. Common reasons for a high PSA level in the blood stream may include prostate cancer, enlarged prostate, and age related inflammation of the prostate or infection of the prostate. Obviously the first concern is to exclude prostate cancer.

Digital Rectal Examination

The bladder is the organ that stores urine and the urethra is the tube that drains urine out through the penis. The prostate lies immediately beneath the bladder and completely surrounds the urethra and lies immediately in front of the rectum (back passage).

Age related enlargement is not a particular concern but if the gland feels abnormally firm or hard, it may sometimes be an indication of an abnormal growth in the prostate gland.

During a digital rectal examination, your doctor inserts a gloved finger into the rectum to feel the condition of the prostate that lies close to the rectal wall. If your doctor feels something suspicious such as a lump or bump, further tests will be carried out.

Your doctor will discuss the test results with you. If he or she detects a suspicious lump or area during the exam, or if your PSA level is elevated, an ultrasound or biopsy may be recommended.

After the test, you may continue your normal activities.

Multi Parametric Prostate MRI

Recent advances have led to better detection of tumours and more accurate targeting of biopsies using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Multi parametric MRI incorporates the use of T2 weighted imaging, diffusion weighted imaging and dynamic contrast imaging. This imaging modality allows spatial resolution and soft tissue contrast necessary to accurately identify prostate cancer. The MRI is non-invasive and lasts approximately 45 minutes.

A multi parametric MRI prior to biopsy can identify suspicious areas which can then be targeted. It should be noted however, that approximately 15% of significant cancers will not be detected by MRI, so standard biopsy techniques would be required in this instance. The MRI can also determine if a cancer in the prostate has spread beyond the prostate into the surrounding tissues or surrounding lymph nodes, which can help with planning surgery or radiotherapy treatment. Multi parametric MRI can also be used to monitor patients with small low grade tumours who have elected to be managed with active surveillance. The results of a multi parametric MRI are highly dependent on the quality of the equipment (3Tesla magnet) and experience of the reading radiologist. Prof Patel refers his patients to facilities which have excellent equipment as well as highly qualified MRI radiologists to obtain reliable information.

If an abnormality is identified on the MRI a number of methods are available to target it at prostate biopsy. The most accurate method is to perform the biopsy under MRI guidance in the MRI scanner. Prof Patel is one of only a small number of urologists in NSW who perform this procedure.

Prostate Biopsy

Prostate biopsy is the removal of cells or tissues of the prostate so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist. The pathologist will check the tissue sample to see if there are cancer cells and find out the Gleason score. The Gleason score ranges from 2-10 and describes how likely it is that a tumour will spread. The lower the number, the less likely the tumour is to spread.

A prostate biopsy can be carried out in 2 different ways:

Transrectal Biopsy

A transrectal biopsy is the removal of tissue from the prostate by inserting a thin needle through the rectum and into the prostate. This procedure is usually done using transrectal ultrasound to help guide where samples of tissue are taken from. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells.

Transperineal Biopsy

By this method the biopsy needle passes through the skin between the scrotum and anus. It is usually performed under general anaesthetic and under ultrasound guidance. This method has the advantage of having a substantially lower risk of infection and better sampling of certain parts of the prostate.

Prostate biopsy may be carried out under MRI guidance. This is the most accurate method of biopsy of a suspicious lesion identified on MRI. It is performed in the MRI scanner. Prof Patel is one of only a small number of urologists in NSW who perform this procedure.

CT Scan

CT scan is basically an x-ray tube that rotates in a circle around the patient and takes a series of pictures as it rotates. The multiple x-ray pictures are reconstructed by a computer in axial slice images at different levels. Each level can be examined separately.

A CT scan may show if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body such as the lymph nodes.

The scan takes from 10-30 minutes. You may be given a drink or injection of a dye, which allows particular areas to be seen more clearly. For a few minutes, this may make you feel hot all over. If you are allergic to iodine or have asthma you could have a more serious reaction to the injection, so it is important to let your doctor know beforehand. You will probably be able to go home as soon as the scan is over.

Bone Scan

Your doctor may want to see if the cancer has metastasised and has affected your bones. A small amount of radioactive material is injected into your arm; abnormal bone absorbs more of the radioactive substance than normal bone and shows up on the scan as highlighted areas (known as ‘hot spots’). Your arm will then be scanned an hour later to view the activity of the bone and ascertain whether the cancer has spread.

The level of radioactivity that is used is very small and does not cause any harm.

This scan can also detect other conditions affecting the bones such as arthritis, so further tests such as an x-ray of the abnormal area may be necessary to confirm that it is cancer.

Prostate Cancer Treatments

Radical Prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy is a surgical procedure to treat prostate cancer and involves removal of the whole prostate gland, seminal vesicles and the surrounding tissues through an incision in the lower abdomen.

Radical prostatectomy can be done either through open approach (a large incision over the abdomen) or through laparoscopy (few small holes over the abdomen), which can also be performed with the assistance of the DaVinci robot.

Active Surveillance

Watchful waiting and active surveillance are treatments used for older men who do not have signs or symptoms or have other medical conditions, and for men whose prostate cancer is found during a screening test.

Watchful waiting is closely monitoring a patient’s condition without giving any treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change. Treatment is given to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

Active surveillance is closely following a patient’s condition without giving any treatment unless there are changes in test results. It is used to find early signs that the condition is getting worse. In active surveillance, patients are given certain exams and tests, including digital rectal exam, PSA test, transrectal ultrasound, and transrectal needle biopsy, to check if the cancer is growing. When the cancer begins to grow, treatment is given to cure the cancer.

Other terms that are used to describe not giving treatment to cure prostate cancer right after diagnosis are observation, watch and wait, and expectant management.

Radiotherapy

External beam radiotherapy

External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer. Conformal radiation is a type of external radiation therapy that uses a computer to create a 3-dimensional (3-D) picture of the tumour.

Seed brachytherapy

Prostate brachytherapy involves the placement of radioactive material directly into the prostate gland. These implants can be in the form or wires or radioactive iodine ‘seeds’.

The seeds are about the size of a grain of rice and are inserted into the prostate through hollow needles placed through the skin below the scrotum. This procedure is generally performed under a general anaesthetic and is called an implant.

Slowly over a few months the seeds deliver a dose of radiation to the prostate cancer.

What is the brachytherapy procedure?

If Prof Patel and his team have decided that you are suitable for brachytherapy, they will first need to plan your treatment.

Initially you will need an ultrasound examination of the prostate. By showing the size and position of the prostate gland, the ultrasound shows precisely where to place the radioactive seeds.

You will then need to return to hospital about six weeks after your ultrasound to have the seeds implanted. You will be admitted to hospital for at least one night after the procedure to ensure that there are no problems with urination.

About three weeks after the implant you will need a CT scan of the prostate; the scan allows doctors to determine the exact dose of radiation given to the prostate.

You will then be followed up every few months, when examinations and PSA tests will be conducted to assess how effective the treatment has been.

What are the side effects of prostate brachytherapy?

It is important to realise that side effects may occur from all treatments.

When undergoing the procedure you will need to undergo at least one general anaesthetic and stay in hospital a minimum of one night.

The level of radiation emitted by the seeds is very low, but as a precaution it is advised that pregnant women and young children maintain a distance of a metre from you (except for short periods – hugs and cuddles) for the first month after the procedure.

Initially you may have slight bleeding from the needle puncture sites and have swelling or bruising around the scrotum. Applying an ice pack can assist in bringing relief and reducing the swelling.

There may be some blood in your urine after your implant, but this generally settles down within a few days. Some men may develop short or long term urinary problems such as obstruction, frequency, urgency and burning urination. This is more common in men who already have some urinary difficulties and is why these men are excluded from brachytherapy.

For a few weeks after treatments you may experience some bowel irritation. This may include frequent or loose motions and/or light bleeding from the rectum.

Advanced Therapy

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy is another option for treating prostate cancer. It is most commonly used in the treatment of malignancies that have spread beyond the prostate.

The body produces hormones to control the growth and activity of healthy cells, but some of these hormones may stimulate the growth of the prostate cancer. The male hormone testosterone, which is produced by the testicles, appears to have a direct effect on the growth of prostate cancer.

Hormone therapy aims to limit the cancers access to testosterone, thereby ‘starving’ the cancer, thus reducing the growth of, or actually shrinking, and the tumour. This means that patients receiving hormone therapy may experience a reduction in their symptoms and possibly a reduction of their tumour that may last for a number of years. Reducing the size of the tumour is also useful when planning radiation therapy of the surgical removal of the prostate.

Testosterone is produced mainly in the testicles and the rate of production is controlled by the pituitary gland in the brain. There are two main methods of reducing the production of these hormones, the surgery method or through medication.

Surgical hormone therapy

Because testosterone is produced by the testicles, the quickest method of reducing its production is by removing part of the testicles; this procedure is known as an ‘Orchiectomy’. Prof Patel will make a small incision in the groin or scrotum while the patient is under general anaesthetic.

While this is a simple procedure that only requires one night in hospital, the recovery period may be painful and there are a number of possible side effects. Most of these symptoms can be treated with medication but there are also the psychological aspects related to the non-reversibility of the procedure to consider.

Medical hormone therapy

Hormone treatment using medication aims to produce the same result as the surgical method, which is to reduce the amount of testosterone available to the cancer. Although this process may take longer than the surgical method, results have shown that the efficacy of this treatment process is the same as the surgical method.

The medications work by suppressing the hormones produced by the pituitary gland in the brain, which stimulate the testes to create testosterone. The hormone drugs can be administered either as tablets or injections that can be administered at home or in hospital either monthly, quarterly or every 6 months.

What are the side effects of hormone therapy?

Both the surgical and medication procedures share common side effects, while there may also be additional side effects related to the medications that you are taking.

Common side effects include hot flushes, tiredness, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction (impotence), weight gain and gynaecomastia (the development of swollen breast tissue).

Most of these side effects can be treated or will pass with time.

It is important to realise that hormone therapy is not a cure and that some cancers can become hormone resistant. It is not known how this happens, but has been noted with both the medical and surgical methods.

Prof Patel will discuss treatment alternatives and possible side effects with you, so that you can make an informed decision about which treatment options are best for you.

Chemotherapy

What is chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy concerns the use of special cytotoxic drugs to treat cancers by either killing the cancer cells or slowing their growth. Chemotherapy drugs travel round the body and attack rapidly growing cells, which may also include healthy cells in the body as well as cancer cells. However the breaks between bouts of chemo allow the body’s normal cells to recover before the next course of chemo.

To travel the body, chemotherapy needs to enter the bloodstream and the quickest way to do this is intravenously – through a vein or artery. Other methods of administering chemotherapy may also take the form of intra-muscular injections, tablets or creams. The way you have chemotherapy depends on a number of factors including the type of cancer you have and the drugs that you are taking. Talk with your doctor if you have any questions about your treatment regime.

Some cancers can be treated or cured by chemotherapy alone, while some treatments may combine chemotherapy with other procedures such as surgery or radiotherapy – this is known as adjuvant therapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy can be used before the main treatment to help make the tumour smaller, or after treatment to kill residual cancer cells that may cause problems later in treatment.

In some instances chemotherapy may not be able to control the cancer but may be used to relieve symptoms such as pain and help you lead as normal a life as is possible.

There are many different combinations of chemotherapy used to treat various cancers, and these may have different effects on different people.

Side effects of chemotherapy

While chemotherapy is useful for the killing of cancer cells in the body, as with most other treatments patients may experience side effects from the chemotherapy. These side effects vary from treatment to treatment and from person to person but fortunately these problems may disappear with time or be managed to reduce the impact that they may cause.

The most common side effects are nausea and vomiting, fatigue (tiredness), alopecia (hair loss), muscular, nerve and blood effects as well as bowel (constipation or diarrhoea) and oral problems.

It is important that you tell the doctors and nurses if you are experiencing any side effects from your treatment so that they can discuss an appropriate course of action with you.

Treatment Options by Stage

Stage I Prostate Cancer

Standard treatment of stage I prostate cancer may include the following:

- Watchful waiting.

- Active surveillance. If the cancer begins to grow, hormone therapy may be given.

- Radical prostatectomy, usually with pelvic lymphadenectomy. Radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- External-beam radiation therapy. Hormone therapy may be given after radiation therapy.

- Brachytherapy with radioactive seeds.

Stage II Prostate Cancer

Standard treatment of stage II prostate cancer may include the following:

- Watchful waiting.

- Active surveillance. If the cancer begins to grow, hormone therapy may be given.

- Radical prostatectomy, usually with pelvic lymphadenectomy. Radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- External-beam radiation therapy. Hormone therapy may be given after radiation therapy.

- Brachytherapy with radioactive seeds.

- Clinical trials of new types of treatment, such as hormone therapy followed by radical prostatectomy.

Stage III Prostate Cancer

Standard treatment of stage III prostate cancer may include the following:

- Radical prostatectomy. Radiation therapy may be given after surgery.

- External-beam radiation therapy. Hormone therapy may be given after radiation therapy.

- Hormone therapy.

- Watchful waiting.

Stage IV Prostate Cancer

Standard treatment of stage IV prostate cancer may include the following:

- Hormone therapy.

- Bisphosphonate therapy.

- External-beam radiation therapy. Hormone therapy may be given after radiation therapy.

- Alpha emitter radiation therapy.

- Watchful waiting.

Treatment to control cancer that is in the prostate and lessen urinary symptoms may include the following:

- Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).

- Radiation therapy.